Have you ever wondered how Cheyenne Mountain Zoo staff members navigate the multitude of opportunities for fun, when they spend their days off at the Zoo? (Yes, we spend our free time here, too.) Well, you’re in luck. CMZoo staff members put together a list of “CMZoo Pro Tips” to help you get the most out of your next visit to America’s mountain Zoo.

Pro Tip #1: Arrive Early

Jane Majeske, CMZoo guest services director, says arriving early is key to a fulfilling and easy-going Zoo experience.

“Mornings at the Zoo are really enjoyable,” Majeske said. “The animals are really active in the morning. They’re waking up, getting breakfast, greeting their keepers and seem excited to start the day.”

Parking is more readily available when we first open. During the peak season’s busy days, Zoo parking can fill up, and free off-site parking and free shuttles usually begin running by 11 a.m.

“You can call the Zoo on your way to find out if we’re running our off-site parking shuttles,” Majeske said. “If they’re already running, we can tell you where to park and catch a shuttle, to save you some time on your way in.”

You can also just watch for helpful temporary signs as you drive up, which will direct you to the free off-site lot we’re using that day.

Bonus Tip: On Saturdays and Sundays, from June 1 through Labor Day, CMZoo members can gain exclusive early entry to the Zoo at 8 a.m. It’s a great time to grab a coffee from The Cozy Goat and to watch the animals greet the day.

Pro Tip #2: Seize the (Imperfect Weather) Day

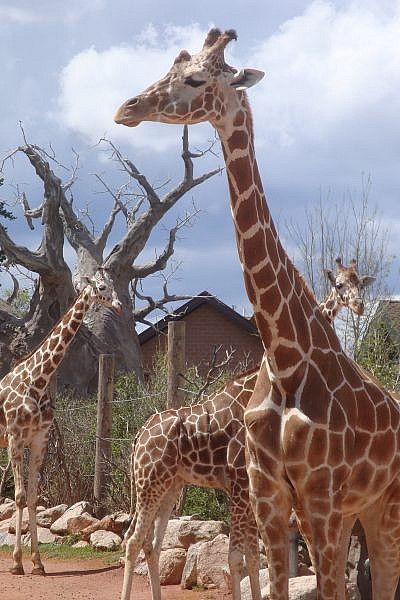

Ilana Cobban, senior lead keeper in Encounter Africa, has worked at the Zoo for 17 years. When she’s not busy caring for CMZoo’s African elephant herd or black rhino, she can sometimes be found enjoying a cloudy day with friends and family at the Zoo.

“My ‘pro tip’ is to not come on a sunny, warm weekend day,” said Cobban. “Come in the middle of the week, when the weather is ‘borderline’ and there are fewer people here and more time for you to take it in. Stick around after animal demonstrations to watch the animals and engage with their keepers, because you never know what you might learn or get to see.”

Pro Tip #3: Check the Animal Happenings Schedule

Overwhelmingly, CMZoo staff says the animal demonstrations and keeper talks provide the best opportunities to connect with CMZoo animals. Daily, every 15 to 30 minutes, from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., there’s a chance to learn about CMZoo animals, directly from the keepers who know them best.

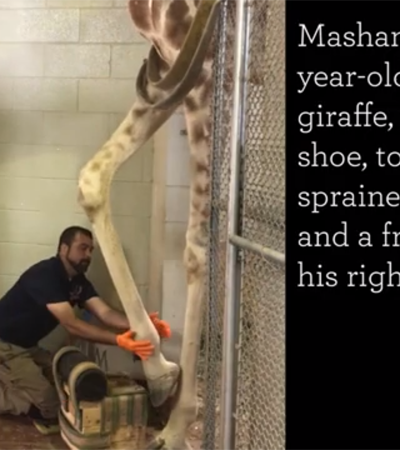

In addition to the all-day animal feeding opportunities for a few extra dollars with giraffe, budgies, chickens and domestic goats, for $10 to $15, guests can participate in CMZoo’s scheduled keeper-led elephant or rhino snack times.

“It’s fun to feed Jumbe, our black rhino, and the African elephants because it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” said Emmaline Repp-Maxwell, CMZoo membership manager. “What’s better than rhino slobber? Nothing.”

Daily at 11:30 a.m. and 2 p.m., guests can get up close with the keepers to feed an elephant. Daily at noon, Jumbe is available for guest feedings.

Amy Schilz, senior lead keeper in African Rift Valley, says her favorite demonstration is the Grizzly Bear demo, ‘The Bear Necessities,’ daily at 2:45 p.m. in Rocky Mountain Wild.

If you’re planning ahead, you can find schedules at cmzoo.org/shows. Or, you can receive the Animal Happenings schedule for any day of the week via text message. Simply text “Zoo + day of the week” to 95577 (i.e. “Zoomonday” or “Zoosaturday”). Standard text message rates apply.

Pro Tip #4: Don’t Forget You’re on a Mountain

Guests, especially those visiting from lower elevations, should remember to bring (and drink) plenty of water and wear sunscreen to enjoy the day in our dry, 6,714-foot-elevation environment. We recommend drinking about 32 ounces of water during a two-hour visit. Bonus points for those who hydrate before they arrive.

If the walk starts to feel like a workout, day shuttle passes are available for $2. Our golf cart shuttles run consistently between shuttle stops established throughout the Zoo. Another way to rest is to have a seat for lunch, and watch an animal demonstration at the same time.

“One good ‘pro tip’ is to grab a picnic table by the carousel outside the Grizzly Grill for lunch,” Michelle Salido, lead keeper in Monkey Pavilion said. “If you time it around 11:45 a.m., those tables are the best place to catch both parts of the ‘Rainforest Review’ monkey demo, without having to move from one spot to another. You can enjoy lunch and a show with some awesome primates.”

Majeske also encourages guests to take a break while the adventure continues on CMZoo’s Mountaineer Sky Ride. For an additional few dollars, guests can enjoy the ski lift-like, 14-minute roundtrip ride with a stop at the top, while they take in amazing views and give their feet a rest.

Pro Tip #5: Go Backwards

Patty Wallace, lead keeper at Water’s Edge: Africa (opening in phases late summer 2019 and fall 2019), says the best way to experience the Zoo is by starting at the top.

“Make your way to the top of the Zoo and start in Encounter Africa, then head to Australia Walkabout,” Wallace said. “If you start there, everything else is downhill. Do the giraffe feeding last and you’ll have more of the exhibit to yourself. Even if giraffe go inside at the end of the day, you can still feed them in their indoor barn.”

Pro Tip #6: Don’t Speed by the Small or Domestic Animals

Carrie Ellis, animal keeper in Primate World, encourages adults to engage in the activities they may think are designed just for the kids.

“Areas like the domestic goat playground, My Big Backyard and The Loft are some of the most fun and interactive places in the whole Zoo,” Ellis said. “Plus, feeding opportunities and keeper talks happen throughout the day, so if you’d rather not stick to the Zoo’s schedule of animal demonstrations, you’ll still get a special experience with our animals.”